The 1947–1948 civil war in Mandatory Palestine was the first phase of the

1947–1949 Palestine war. It broke out after the

General Assembly

A general assembly or general meeting is a meeting of all the members of an organization or shareholders of a company.

Specific examples of general assembly include:

Churches

* General Assembly (presbyterian church), the highest court of presb ...

of the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

adopted a resolution on 29 November 1947 recommending the adoption of the

Partition Plan for Palestine.

During the civil war, the

Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

and

Arab communities of

Palestine clashed (the latter supported by the

Arab Liberation Army

The Arab Liberation Army (ALA; ar, جيش الإنقاذ العربي ''Jaysh al-Inqadh al-Arabi''), also translated as Arab Salvation Army, was an army of volunteers from Arab countries led by Fawzi al-Qawuqji. It fought on the Arab side in the ...

) while the British, who had the obligation to maintain order,

organized their withdrawal and intervened only on an occasional basis.

When the

British Mandate of Palestine British Mandate of Palestine or Palestine Mandate most often refers to:

* Mandate for Palestine: a League of Nations mandate under which the British controlled an area which included Mandatory Palestine and the Emirate of Transjordan.

* Mandatory P ...

expired on 14 May 1948, and with the

Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel

The Israeli Declaration of Independence, formally the Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel ( he, הכרזה על הקמת מדינת ישראל), was proclaimed on 14 May 1948 ( 5 Iyar 5708) by David Ben-Gurion, the Executive ...

, the surrounding Arab states—

Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

,

Transjordan Transjordan may refer to:

* Transjordan (region), an area to the east of the Jordan River

* Oultrejordain, a Crusader lordship (1118–1187), also called Transjordan

* Emirate of Transjordan, British protectorate (1921–1946)

* Hashemite Kingdom of ...

,

Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

and

Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

—invaded what had just ceased to be Mandatory Palestine,

[ Benny Morris (2008), p. 180 and further] and immediately attacked Israeli forces and several Jewish settlements.

The conflict thus escalated and became the

1948 Arab–Israeli War

The 1948 (or First) Arab–Israeli War was the second and final stage of the 1948 Palestine war. It formally began following the end of the British Mandate for Palestine at midnight on 14 May 1948; the Israeli Declaration of Independence had ...

.

Background

Under the control of a British administration since 1920, Palestine found itself the object of a battle between

Palestinian

Palestinians ( ar, الفلسطينيون, ; he, פָלַסְטִינִים, ) or Palestinian people ( ar, الشعب الفلسطيني, label=none, ), also referred to as Palestinian Arabs ( ar, الفلسطينيين العرب, label=non ...

and

Zionist

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after '' Zion'') is a nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in Je ...

nationalists, groups that opposed both the British mandate and one another.

The Palestinian backlash culminated in the

1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine

The 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine, later known as The Great Revolt (''al-Thawra al- Kubra'') or The Great Palestinian Revolt (''Thawrat Filastin al-Kubra''), was a popular nationalist uprising by Palestinian Arabs in Mandatory Palestine a ...

, a deadly civil conflict that saw the deaths of nearly 5,000 Palestinian Arabs and 500 Jews, and resulted in much of the Palestinian political leadership, including

Amin al-Husseini

Mohammed Amin al-Husseini ( ar, محمد أمين الحسيني 1897

– 4 July 1974) was a Palestinian Arab nationalist and Muslim leader in Mandatory Palestine.

Al-Husseini was the scion of the al-Husayni family of Jerusalemite Arab notab ...

, leader of the

Arab Higher Committee, being driven into exile. Britain also reduced Jewish immigration in response to the violence, as legislated by the

1939 White Paper. It also prompted the reinforcement of Zionist paramilitary groups.

After World War II and

The Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; a ...

, the

Zionist movement

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after ''Zion'') is a nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in Jew ...

gained attention and sympathy. In Mandatory Palestine, Zionist groups

fought against the British occupation. In the two and a half years from 1945 to June 1947, British law enforcement forces lost 103 dead, and sustained 391 wounded from Jewish militants. The Palestinian Arab nationalists reorganized themselves, but their organization remained inferior to that of the Zionists. Nevertheless, the weakening of the colonial British Empire reinforced Arab countries and the

Arab League

The Arab League ( ar, الجامعة العربية, ' ), formally the League of Arab States ( ar, جامعة الدول العربية, '), is a regional organization in the Arab world, which is located in Northern Africa, Western Africa, E ...

.

The

Haganah

Haganah ( he, הַהֲגָנָה, lit. ''The Defence'') was the main Zionist paramilitary organization of the Jewish population ("Yishuv") in Mandatory Palestine between 1920 and its disestablishment in 1948, when it became the core of the ...

, a Jewish paramilitary organization, was initially involved in the post-war attacks against the British in Palestine but withdrew following the outrage caused by the 1946

Irgun

Irgun • Etzel

, image = Irgun.svg , image_size = 200px

, caption = Irgun emblem. The map shows both Mandatory Palestine and the Emirate of Transjordan, which the Irgun claimed in its entirety for a future Jewish state. The acronym "Etzel" i ...

bombing of the British Army Headquarters in the

King David Hotel

The King David Hotel ( he, מלון המלך דוד, Malon ha-Melekh David; ar, فندق الملك داود) is a 5-star hotel in Jerusalem and a member of The Leading Hotels of the World. Opened in 1931, the hotel was built with locally qua ...

.

In May 1946, on the assumption of British neutrality in the future hostilities, a Plan C was formulated that envisaged guidelines for retaliation if and when Palestinian Arab attacks took place on the

Yishuv

Yishuv ( he, ישוב, literally "settlement"), Ha-Yishuv ( he, הישוב, ''the Yishuv''), or Ha-Yishuv Ha-Ivri ( he, הישוב העברי, ''the Hebrew Yishuv''), is the body of Jewish residents in the Land of Israel (corresponding to the s ...

. As the countdown ticked down, the Haganah implemented assaults involving the torching and demolition by explosives against economic infrastructures, the property of Palestinian politicians and military commanders, villages, town neighbourhoods, houses and farms that were deemed to be bases or used by inciters and their accomplices. The killing of armed irregulars and adult males was also foreseen.

On 15 August 1947, on suspicion it was a terrorist headquarters, they blew up the house of the Abu Laban family, prosperous Palestinian orange growers, near

Petah Tikva

Petah Tikva ( he, פֶּתַח תִּקְוָה, , ), also known as ''Em HaMoshavot'' (), is a city in the Central District (Israel), Central District of Israel, east of Tel Aviv. It was founded in 1878, mainly by Haredi Judaism, Haredi Jews of ...

. Twelve occupants, including a woman and six children, were killed. After November 1947, the dynamiting of houses formed a key component of most Haganah retaliatory strikes.

Diplomacy failed to reconcile the different points of view concerning the future of Palestine. On 18 February 1947, the British announced their withdrawal from the region. Later that year, on 29 November, the General Assembly of the United Nations voted to recommend the adoption and implementation of the

partition plan with the support of the big global powers, but not of Britain nor of the Arab States.

Beginning of the civil war (30 November 1947 – 1 April 1948)

In the aftermath of the

adoption of Resolution 181(II) by the

United Nations General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; french: link=no, Assemblée générale, AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as the main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ of the UN. Curr ...

recommending the adoption and implementation of the Plan of Partition, the manifestations of joy of the Jewish community were counterbalanced by protests by Arabs throughout the country and after 1 December, the

Arab Higher Committee enacted a

general strike

A general strike refers to a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large co ...

that lasted three days.

A "wind of violence" rapidly took hold of the country, foreboding civil war between the two communities. Murders, reprisals, and counter-reprisals came fast on each other's heels, resulting in dozens of victims killed on both sides in the process. The impasse persisted as British forces did not intervene to put a stop to the escalating cycles of violence.

[Morris 2008, p. 76][ Efraïm Karsh (2002), p. 30][ Benny Morris (2003), p. 101]

The first casualties after the adoption of Resolution 181(II) were passengers on a Jewish bus near

Kfar Sirkin

Kfar Sirkin or Kefar Syrkin ( he, כְּפַר סִירְקִין) is a moshav in central Israel. Located south-east of Petah Tikva, it falls under the jurisdiction of Drom HaSharon Regional Council. In it had a population of .

History

Kfar Sirk ...

on 30 November, after an eight-man gang from Jaffa

ambushed the bus killing five and wounding others. Half an hour later they ambushed a second bus, southbound from

Hadera

Hadera ( he, חֲדֵרָה ) is a city located in the Haifa District of Israel, in the northern Sharon region, approximately 45 kilometers (28 miles) from the major cities of Tel Aviv and Haifa. The city is located along 7 km (5&nb ...

, killing two more, and shots were fired at Jewish buses in Jerusalem and Haifa.

This was stated to be a retaliation for the

Shubaki family assassination, the killing of five Palestinian Arabs by

Lehi near

Herzliya

Herzliya ( ; he, הֶרְצְלִיָּה ; ar, هرتسليا, Hirtsiliyā) is an affluent city in the central coast of Israel, at the northern part of the Tel Aviv District, known for its robust start-up and entrepreneurial culture. In it h ...

, ten days' prior to the incident.

Irgun

Irgun • Etzel

, image = Irgun.svg , image_size = 200px

, caption = Irgun emblem. The map shows both Mandatory Palestine and the Emirate of Transjordan, which the Irgun claimed in its entirety for a future Jewish state. The acronym "Etzel" i ...

and

Lehi (the latter also known as the Stern Gang) followed their strategy of placing bombs in crowded markets and bus-stops. On 30 December, in Haifa, members of the

Irgun

Irgun • Etzel

, image = Irgun.svg , image_size = 200px

, caption = Irgun emblem. The map shows both Mandatory Palestine and the Emirate of Transjordan, which the Irgun claimed in its entirety for a future Jewish state. The acronym "Etzel" i ...

threw two bombs at a crowd of Arab workers who were queueing in front of a refinery, killing 6 and injuring 42. An angry crowd

massacred 39 Jewish people in revenge, until British soldiers reestablished calm.

In reprisals, some soldiers from the strike force,

Palmach and the

Carmeli brigade 2nd "Carmeli" Brigade (Hebrew: חטיבת כרמלי, Hativat Carmeli, former 165th Brigade) is a reserve infantry brigade of the Israel Defense Forces, part of the Northern Command. Today the brigade consists of four battalions, including one recon ...

,

attacked the villages of Balad ash-Sheikh and Hawassa. According to different historians, this attack led to between 21 and 70 deaths.

According to

Benny Morris, an Israeli historian, much of the fighting in the first months of the war took place in and on the edges of the main towns, and was initiated by the Arabs. It included Arab snipers firing at Jewish houses, pedestrians, and traffic, as well as planting bombs and mines along urban and rural paths and roads.

[ Benny Morris (2008), p. 101]

From January onward, operations became increasingly militarized. In all the mixed zones where both communities lived, particularly

Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

and

Haifa

Haifa ( he, חֵיפָה ' ; ar, حَيْفَا ') is the third-largest city in Israel—after Jerusalem and Tel Aviv—with a population of in . The city of Haifa forms part of the Haifa metropolitan area, the third-most populous metropol ...

, increasingly violent attacks,

riots, reprisals and counter-reprisals followed each other. Isolated shootings evolved into all-out

battle

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

s. Attacks against traffic, for instance, turned into ambushes as one bloody attack led to another.

On 22 February 1948, supporters of

Mohammad Amin al-Husayni

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mono ...

organized, with the help of certain British deserters, three attacks against the Jewish community. Using

car bomb

A car bomb, bus bomb, lorry bomb, or truck bomb, also known as a vehicle-borne improvised explosive device (VBIED), is an improvised explosive device designed to be detonated in an automobile or other vehicles.

Car bombs can be roughly divided ...

s aimed at the headquarters of the pro-Zionist ''

Palestine Post'' newspaper, the

Ben Yehuda St. market and the backyard of the Jewish Agency's offices, they killed 22, 53, and 13 Jewish people respectively, a total of 88 fatalities. Hundreds of others were injured.

In retaliation,

Lehi put a

landmine on the railroad track in

Rehovot on which a train from

Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metro ...

to

Haifa

Haifa ( he, חֵיפָה ' ; ar, حَيْفَا ') is the third-largest city in Israel—after Jerusalem and Tel Aviv—with a population of in . The city of Haifa forms part of the Haifa metropolitan area, the third-most populous metropol ...

was travelling, killing 28 British soldiers and injuring 35. This would be copied on 31 March, close to

Caesarea Maritima

Caesarea Maritima (; Greek: ''Parálios Kaisáreia''), formerly Strato's Tower, also known as Caesarea Palestinae, was an ancient city in the Sharon plain on the coast of the Mediterranean, now in ruins and included in an Israeli national park ...

, which would lead to the death of forty people, injuring 60, who were, for the most part, Arab civilians.

Having recruited a few thousand volunteers, al-Husayni organized the blockade of the 100,000 Jewish residents of Jerusalem.

[ Dominique Lapierre et Larry Collins (1971), chap. 7, pp. 131–153] To counter this, the

Yishuv

Yishuv ( he, ישוב, literally "settlement"), Ha-Yishuv ( he, הישוב, ''the Yishuv''), or Ha-Yishuv Ha-Ivri ( he, הישוב העברי, ''the Hebrew Yishuv''), is the body of Jewish residents in the Land of Israel (corresponding to the s ...

authorities tried to supply the city with convoys of up to 100 armoured vehicles, but the operation became more and more impractical as the number of casualties in the relief convoys surged. By March, Al-Hussayni's tactic had paid off. Almost all of the Haganah's armoured vehicles had been destroyed, the blockade was in full operation, and hundreds of Haganah members who had tried to bring supplies into the city were killed.

[ Benny Morris (2003), p. 163] The situation for those who dwelt in the Jewish settlements in the highly isolated

Negev

The Negev or Negeb (; he, הַנֶּגֶב, hanNegév; ar, ٱلنَّقَب, an-Naqab) is a desert and semidesert region of southern Israel. The region's largest city and administrative capital is Beersheba (pop. ), in the north. At its southe ...

and North of Galilee was even more critical.

According to the

Arab League

The Arab League ( ar, الجامعة العربية, ' ), formally the League of Arab States ( ar, جامعة الدول العربية, '), is a regional organization in the Arab world, which is located in Northern Africa, Western Africa, E ...

general Safwat:

Despite the fact that skirmishes and battles have begun, the Jews at this stage are still trying to contain the fighting to as narrow a sphere as possible in the hope that partition will be implemented and a Jewish government formed; they hope that if the fighting remains limited, the Arabs will acquiesce in the fait accompli. This can be seen from the fact that the Jews have not so far attacked Arab villages unless the inhabitants of those villages attacked them or provoked them first.

David Ben-Gurion

David Ben-Gurion ( ; he, דָּוִד בֶּן-גּוּרִיּוֹן ; born David Grün; 16 October 1886 – 1 December 1973) was the primary national founder of the State of Israel and the first prime minister of Israel. Adopting the nam ...

reorganized the Haganah and made conscription obligatory. Every Jewish man and woman in the country had to receive military training.

Allied Powers' policies

This situation caused the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

to withdraw their support for the Partition plan, thus encouraging the

Arab League

The Arab League ( ar, الجامعة العربية, ' ), formally the League of Arab States ( ar, جامعة الدول العربية, '), is a regional organization in the Arab world, which is located in Northern Africa, Western Africa, E ...

to believe that the Palestinian Arabs, reinforced by the Arab Liberation Army, could put an end to the plan for partition. The British, on the other hand, decided on 7 February 1948, to support the annexation of the Arab part of Palestine by

Transjordan Transjordan may refer to:

* Transjordan (region), an area to the east of the Jordan River

* Oultrejordain, a Crusader lordship (1118–1187), also called Transjordan

* Emirate of Transjordan, British protectorate (1921–1946)

* Hashemite Kingdom of ...

.

[ Henry Laurens (2005), p. 83]

Population evacuations

While the Jewish population had received strict orders requiring them to hold their ground everywhere at all costs,

[ Dominique Lapierre et Larry Collins (1971), p. 163] the Arab population was more affected by the general conditions of insecurity to which the country was exposed. Up to 100,000 Arabs, from the urban upper and middle classes in Haifa, Jaffa and Jerusalem, or Jewish-dominated areas, evacuated abroad or to Arab centres eastwards.

[ Benny Morris (2003), p. 67]

Fighters and arms from abroad

As a consequence of funds raised by

Golda Meir

Golda Meir, ; ar, جولدا مائير, Jūldā Māʾīr., group=nb (born Golda Mabovitch; 3 May 1898 – 8 December 1978) was an Israeli politician, teacher, and ''kibbutznikit'' who served as the fourth prime minister of Israel from 1969 to 1 ...

which were donated by sympathisers in the United States, and

Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

's decision to support the

Zionist

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after '' Zion'') is a nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in Je ...

cause, the Jewish representatives of Palestine were able to sign very important armament contracts in the East. Other Haganah agents recuperated stockpiles from the Second World War, which helped improve the army's equipment and logistics.

Operation Balak

Operation Balak was a smuggling operation, during the founding of Israel in 1948, that purchased arms in Europe to avoid various embargoes and boycotts transferring them to the Yishuv. Of particular note was the delivery of 23 Czechoslovakia-made ...

allowed arms and other equipment to be transported for the first time by the end of March.

There was an intervention of a number of

Arab Liberation Army

The Arab Liberation Army (ALA; ar, جيش الإنقاذ العربي ''Jaysh al-Inqadh al-Arabi''), also translated as Arab Salvation Army, was an army of volunteers from Arab countries led by Fawzi al-Qawuqji. It fought on the Arab side in the ...

regiments inside Palestine, each active in a variety of distinct sectors around the different coastal towns. They consolidated their presence in

Galilee

Galilee (; he, הַגָּלִיל, hagGālīl; ar, الجليل, al-jalīl) is a region located in northern Israel and southern Lebanon. Galilee traditionally refers to the mountainous part, divided into Upper Galilee (, ; , ) and Lower Galil ...

and

Samaria

Samaria (; he, שֹׁמְרוֹן, translit=Šōmrōn, ar, السامرة, translit=as-Sāmirah) is the historic and biblical name used for the central region of Palestine, bordered by Judea to the south and Galilee to the north. The first- ...

.

[ Yoav Gelber (2006), pp. 51–56] Abd al-Qadir al-Husayni

Abd al-Qadir al-Husayni ( ar, عبد القادر الحسيني), also spelled Abd al-Qader al-Husseini (1907 – 8 April 1948) was a Palestinian Arab nationalist and fighter who in late 1933 founded the secret militant group known as the Orga ...

came from Egypt with several hundred men of the

Army of the Holy War.

German and Bosnian WWII veterans, including a handful of former intelligence,

Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previous ...

, and

Waffen SS

The (, "Armed SS") was the combat branch of the Nazi Party's ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) organisation. Its formations included men from Nazi Germany, along with volunteers and conscripts from both occupied and unoccupied lands.

The grew from th ...

officers, were among the volunteers fighting for the Palestinian cause. Veterans of WWII

Axis

An axis (plural ''axes'') is an imaginary line around which an object rotates or is symmetrical. Axis may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Axis of rotation: see rotation around a fixed axis

* Axis (mathematics), a designator for a Cartesian-coordinat ...

militaries were represented in the ranks of the ALA forces commanded by

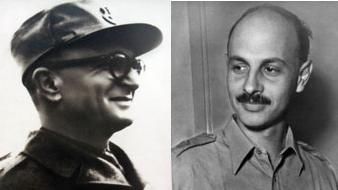

Fawzi al-Qawuqji (who had been awarded an officer's rank in the Wehrmacht during WWII)

["Ruhmloses Zwischenspiel: Fawzi al-Qawuqji in Deutschland, 1941–1947", by Gerhard Höpp in Peter Heine, ed., Al-Rafidayn: Jahrbuch zu Geschichte und Kultur des modernen Iraq (Würzburg: Ergon Verlag, 1995),]

, p. 16 and in the Mufti's forces, commanded by Abd al-Qadir (who had fought with the Germans against the British in Iraq) and Salama (who trained in Germany as a commando during WWII and took part in a failed

Operation Atlas (Mandatory Palestine), parachute mission into Palestine).

Benny Morris writes that the Yishuv was more successful in attracting and effectively deploying foreign military professionals than their Arab adversaries. He concludes that the ex-Nazis and Bosnian Muslims recruited by the Palestinians, Egyptians, and Syrians "proved of little significance" to the outcome of the conflict.

Death toll

In December, the Jewish death toll was estimated at over 200, and, according to

Alec Kirkbride

Sir Alec Seath Kirkbride (1897–1978) was a British diplomat, a proconsul, who served in Jordan and Palestine between 1920 and 1951.

Biography

Kirkbride was born in Mansfield, Nottinghamshire, on 19 August 1897 to British parents and grew ...

, by 18 January, 333 Jews and 345 Arabs had been killed while 643 Jews and 877 Arabs had been injured. The overall death toll between December 1947 and January 1948 (including British personnel) was estimated at around 1,000 people, with 2,000 injured.

Ilan Pappé

Ilan Pappé ( he, אילן פפה, ; born 1954) is an expatriate Israeli historian and socialist activist. He is a professor with the College of Social Sciences and International Studies at the University of Exeter in the United Kingdom, direc ...

estimates that 400 Jews and 1,500 Arabs were killed by January 1948.

[ Ilan Pappe (2006), p. 72.] Morris says that by the end of March 1948, the Yishuv had suffered about a thousand dead.

[ Benny Morris (2008), p. 112] According to Yoav Gelber, by the end of March there was a total of 2,000 dead and 4,000 wounded.

These figures correspond to an average of more than 100 deaths and 200 casualties per week among a population of 2,000,000.

Intervention of foreign forces in Palestine

Violence kept intensifying with the intervention of military units. Although responsible for law and order up until the end of the mandate, the British did not try to take control of the situation, being more involved in the liquidation of the administration and the evacuation of their troops. Furthermore, the authorities felt that they had lost enough men already in the conflict.

The British either could not or did not want to impede the intervention of foreign forces into Palestine. According to a special report by the UN Special Commission on Palestine:

* During the night of 20–21 January, a force of 700

Syrians in battle dress, well-equipped, with mechanized transport, entered Palestine 'via

Transjordan Transjordan may refer to:

* Transjordan (region), an area to the east of the Jordan River

* Oultrejordain, a Crusader lordship (1118–1187), also called Transjordan

* Emirate of Transjordan, British protectorate (1921–1946)

* Hashemite Kingdom of ...

.'

* On 27 January, 'a band of 300 men from outside Palestine, was established in the area of

Safed

Safed (known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as Tzfat; Sephardi Hebrew, Sephardic Hebrew & Modern Hebrew: צְפַת ''Tsfat'', Ashkenazi Hebrew pronunciation, Ashkenazi Hebrew: ''Tzfas'', Biblical Hebrew: ''Ṣǝp̄aṯ''; ar, صفد, ''Ṣafad''), i ...

in

Galilee

Galilee (; he, הַגָּלִיל, hagGālīl; ar, الجليل, al-jalīl) is a region located in northern Israel and southern Lebanon. Galilee traditionally refers to the mountainous part, divided into Upper Galilee (, ; , ) and Lower Galil ...

and was probably responsible for the intensive heavy weapon and

mortar attacks the following week against the settlement of Yechiam.'

* During the night of 29–30 January, a battalion of the

Arab Liberation Army

The Arab Liberation Army (ALA; ar, جيش الإنقاذ العربي ''Jaysh al-Inqadh al-Arabi''), also translated as Arab Salvation Army, was an army of volunteers from Arab countries led by Fawzi al-Qawuqji. It fought on the Arab side in the ...

, 950 men in 19 vehicles commanded by Fawzi al-Qawuqji, entered Palestine 'via

Adam Bridge and dispersed itself around the villages of

Nablus

Nablus ( ; ar, نابلس, Nābulus ; he, שכם, Šəḵem, ISO 259-3: ; Samaritan Hebrew: , romanized: ; el, Νεάπολις, Νeápolis) is a Palestinian city in the West Bank, located approximately north of Jerusalem, with a populati ...

,

Jenin, and

Tulkarem

Tulkarm, Tulkarem or Tull Keram ( ar, طولكرم, ''Ṭūlkarm'') is a Palestinian city in the West Bank, located in the Tulkarm Governorate of the State of Palestine. The Israeli city of Netanya is to the west, and the Palestinian cities of ...

.'

This description corresponds to the entry of Arab Liberation Army troops between 10 January and the start of March:

* The Second regiment of

Yarmouk, under the orders of

Adib Shishakli

Adib al-Shishakli (1909 – 27 September 1964 ar, أديب الشيشكلي, ʾAdīb aš-Šīšaklī) was a Syrian military leader and President of Syria from 1953 to 1954.

Early life

Adib Shishakli was born (1909) in the Hama Sanjak of Ott ...

entered

Galilee

Galilee (; he, הַגָּלִיל, hagGālīl; ar, الجليل, al-jalīl) is a region located in northern Israel and southern Lebanon. Galilee traditionally refers to the mountainous part, divided into Upper Galilee (, ; , ) and Lower Galil ...

via

Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus li ...

on the night of 11–12 January. The battalion passed through

Safed

Safed (known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as Tzfat; Sephardi Hebrew, Sephardic Hebrew & Modern Hebrew: צְפַת ''Tsfat'', Ashkenazi Hebrew pronunciation, Ashkenazi Hebrew: ''Tzfas'', Biblical Hebrew: ''Ṣǝp̄aṯ''; ar, صفد, ''Ṣafad''), i ...

and then settled in the village of Sasa. A third of the regiment's fighters were Palestinian Arabs, and a quarter were

Syrian.

* The 1st Yarmouk regiment, commanded by Muhammad Tzafa, entered Palestine on the night of 20–21 January, via the Bridge of Damia from Jordan and dispersed around

Samaria

Samaria (; he, שֹׁמְרוֹן, translit=Šōmrōn, ar, السامرة, translit=as-Sāmirah) is the historic and biblical name used for the central region of Palestine, bordered by Judea to the south and Galilee to the north. The first- ...

, where it established its HQ, in the Northern Samarian city of

Tubas

A tuba is a musical instrument that plays notes in the bass clef.

Tuba can also refer to:

Instruments

*Roman tuba, a straight trumpet of ancient Rome

*Tuba curva, a revival of the Roman ''cornu''

*Wagner tuba, an instrument like the tuba curva ...

. The regiment was composed chiefly of Palestinian Arabs and

Iraqis

Iraqis ( ar, العراقيون, ku, گهلی عیراق, gelê Iraqê) are people who originate from the country of Iraq. Iraq consists largely of most of ancient Mesopotamia, the native land of the indigenous Sumerian, Akkadian, Assyrian, ...

.

* The Hittin regiment, commanded by Madlul Abbas, settled in the west of Samaria with its headquarters in

Tulkarem

Tulkarm, Tulkarem or Tull Keram ( ar, طولكرم, ''Ṭūlkarm'') is a Palestinian city in the West Bank, located in the Tulkarm Governorate of the State of Palestine. The Israeli city of Netanya is to the west, and the Palestinian cities of ...

.

* The Hussein ibn Ali regiment provided reinforcement in

Haifa

Haifa ( he, חֵיפָה ' ; ar, حَيْفَا ') is the third-largest city in Israel—after Jerusalem and Tel Aviv—with a population of in . The city of Haifa forms part of the Haifa metropolitan area, the third-most populous metropol ...

,

Jaffa

Jaffa, in Hebrew Yafo ( he, יָפוֹ, ) and in Arabic Yafa ( ar, يَافَا) and also called Japho or Joppa, the southern and oldest part of Tel Aviv-Yafo, is an ancient port city in Israel. Jaffa is known for its association with the b ...

,

Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

, and several other cities.

* The Qadassia regiment were reserves based in Jab'a.

Fawzi al-Qawuqji, Field Commander of the Arab Liberation Army, arrived, according to his own account, on 4 March, with the rest of the logistics and around 100

Bosniak volunteers in Jab'a, a small village on the route between

Nablus

Nablus ( ; ar, نابلس, Nābulus ; he, שכם, Šəḵem, ISO 259-3: ; Samaritan Hebrew: , romanized: ; el, Νεάπολις, Νeápolis) is a Palestinian city in the West Bank, located approximately north of Jerusalem, with a populati ...

and

Jenin. He established a headquarters there and a training centre for Palestinian Arab volunteers.

Alan Cunningham

General (United Kingdom), General Sir Alan Gordon Cunningham, (1 May 1887 – 30 January 1983) was a senior Officer (armed forces), officer of the British Army noted for his victories over Italian forces in the East African Campaign (World War ...

, the British

High Commissioner in Palestine, thoroughly protested against the incursions and the fact that 'no serious effort is being made to stop incursions'. The only reaction came from Alec Kirkbride, who complained to

Ernest Bevin

Ernest Bevin (9 March 1881 – 14 April 1951) was a British statesman, trade union leader, and Labour Party politician. He co-founded and served as General Secretary of the powerful Transport and General Workers' Union in the years 1922–19 ...

about Cunningham's "hostile tone and threats".

The British and the information service of Yishuv expected an offensive for 15 February, but it would not take place, seemingly because the Mufti troops were not ready.

In March, an Iraqi regiment of the Arab Liberation Army came to reinforce the Palestinian Arab troops of

Salameh in the area around

Lydda

Lod ( he, לוד, or fully vocalized ; ar, اللد, al-Lidd or ), also known as Lydda ( grc, Λύδδα), is a city southeast of Tel Aviv and northwest of Jerusalem in the Central District of Israel. It is situated between the lower Sheph ...

and

Ramleh

Ramla or Ramle ( he, רַמְלָה, ''Ramlā''; ar, الرملة, ''ar-Ramleh'') is a city in the Central District of Israel. Today, Ramle is one of Israel's mixed cities, with both a significant Jewish and Arab populations.

The city was f ...

, while Al-Hussayni started a headquarters in Bir Zeit, 10 km to the north of Ramallah.

[ Yoav Gelber (2006), p. 56] At the same time, a number of North African troops, principally

Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya bo ...

ns, and hundreds of members of the

Muslim Brotherhood entered Palestine. In March, an initial regiment arrived in

Gaza and certain militants among them reached

Jaffa

Jaffa, in Hebrew Yafo ( he, יָפוֹ, ) and in Arabic Yafa ( ar, يَافَا) and also called Japho or Joppa, the southern and oldest part of Tel Aviv-Yafo, is an ancient port city in Israel. Jaffa is known for its association with the b ...

.

Morale of the fighters

The Arab combatants' initial victories reinforced morale among them.

[ United Nations Special Commission (16 February 1948), § II.7.3] The

Arab Higher Committee was confident and decided to prevent the set-up of the UN-backed partition plan. In an announcement made to the Secretary-General on 6 February, they declared:

At the beginning of February 1948, the morale of the Jewish leaders was not high: "distress and despair arose clearly from the notes taken at the meetings of the Mapai party." "The attacks against the Jewish settlements and main roads worsened the direction of the Jewish people, who underestimated the intensity of the Arab reaction."

The situation of the 100,000 Jews situated in

Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

was precarious, and supplies to the city, already slim in number, were likely to be stopped. Nonetheless, despite the setbacks suffered, the Jewish forces, in particular

Haganah

Haganah ( he, הַהֲגָנָה, lit. ''The Defence'') was the main Zionist paramilitary organization of the Jewish population ("Yishuv") in Mandatory Palestine between 1920 and its disestablishment in 1948, when it became the core of the ...

, remained superior in number and quality to those of the Arab forces.

First wave of Palestinian refugees

The high morale of the Arab fighters and politicians was not shared by the Palestinian Arab civilian population. The UN Palestine Commission reported 'Panic continues to increase, however, throughout the Arab middle classes, and there is a steady exodus of those who can afford to leave the country.

'From December 1947 to January 1948, around 70,000 Arabs fled, and, by the end of March, that number had grown to around 100,000.

These people were part of the first wave of Palestinian refugees of the conflict. Mostly the middle and upper classes fled, including the majority of the families of local governors and representatives of the

Arab Higher Committee.

Non-Palestinian Arabs also fled in large numbers. Most of them did not abandon the hope of returning to Palestine once the hostilities had ended.

Policies of foreign powers

Many decisions were made abroad that had an important influence over the outcome of the conflict.

Britain and the Jordanian choice

Britain did not want a Palestinian state led by the

Mufti

A Mufti (; ar, مفتي) is an Islamic jurist qualified to issue a nonbinding opinion ('' fatwa'') on a point of Islamic law (''sharia''). The act of issuing fatwas is called ''iftāʾ''. Muftis and their ''fatwas'' played an important rol ...

, and opted unofficially instead, on 7 February 1948, to support the annexation of the Arab part of Palestine by

Abdullah I of Jordan

AbdullahI bin Al-Hussein ( ar, عبد الله الأول بن الحسين, translit=Abd Allāh al-Awwal bin al-Husayn, 2 February 1882 – 20 July 1951) was the ruler of Jordan from 11 April 1921 until his assassination in 1951. He was the Emi ...

.

At a meeting in London between the commander of

Transjordan Transjordan may refer to:

* Transjordan (region), an area to the east of the Jordan River

* Oultrejordain, a Crusader lordship (1118–1187), also called Transjordan

* Emirate of Transjordan, British protectorate (1921–1946)

* Hashemite Kingdom of ...

's

Arab Legion

The Arab Legion () was the police force, then regular army of the Emirate of Transjordan, a British protectorate, in the early part of the 20th century, and then of independent Jordan, with a final Arabization of its command taking place in 195 ...

,

Glubb Pasha

Lieutenant-General Sir John Bagot Glubb, KCB, CMG, DSO, OBE, MC, KStJ, KPM (16 April 1897 – 17 March 1986), known as Glubb Pasha, was a British soldier, scholar, and author, who led and trained Transjordan's Arab Legion between 1939 a ...

, and

Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs

The secretary of state for foreign, Commonwealth and development affairs, known as the foreign secretary, is a minister of the Crown of the Government of the United Kingdom and head of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. Seen as ...

,

Ernest Bevin

Ernest Bevin (9 March 1881 – 14 April 1951) was a British statesman, trade union leader, and Labour Party politician. He co-founded and served as General Secretary of the powerful Transport and General Workers' Union in the years 1922–19 ...

, the two parties agreed that they would facilitate the entry of the Arab Legion into Palestine on 15 May and that the Arab part of Palestine be occupied by it. However, they held that the Arab Legion not enter the vicinity of Jerusalem or the Jewish state itself.

This option did not envisage a Palestinian Arab state. Although the ambitions of King Abdullah are known, it is not apparent to what extent the authorities of Yishuv, the

Arab Higher Committee or the

Arab League

The Arab League ( ar, الجامعة العربية, ' ), formally the League of Arab States ( ar, جامعة الدول العربية, '), is a regional organization in the Arab world, which is located in Northern Africa, Western Africa, E ...

knew of this decision.

United States turnabout

In mid-March, after the increasing disorder in Palestine and faced with the fear, later judged unfounded, of an Arab petrol embargo, the US government announced the possible withdrawal of its support for the UN's partition plan and for dispatching an international force to guarantee its implementation. The US suggested that instead Palestine be put under

UN supervision. On 1 April, the

UN Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the Organs of the United Nations, six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international security, international peace and security, recommending the admi ...

voted on the US proposal to convoke a special assembly to reconsider the Palestinian problem; the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

abstained. This U-turn by the US caused concern and debate among Yishuv authorities. They thought that after the withdrawal of British troops, the Yishuv could not effectively resist the Arab forces without the support of the US. In this context, Elie Sasson, the director of the Arab section of

Jewish Agency

The Jewish Agency for Israel ( he, הסוכנות היהודית לארץ ישראל, translit=HaSochnut HaYehudit L'Eretz Yisra'el) formerly known as The Jewish Agency for Palestine, is the largest Jewish non-profit organization in the world. ...

, and several other personalities, persuaded David Ben-Gurion and

Golda Meyerson to advance a diplomatic initiative to the Arabs. The job of negotiation was delegated to Joshua Palmon, who was prohibited from limiting the Haganah's liberty of action but was authorized to declare that "the Jewish people were ready with a truce."

Logistical support of the Eastern Bloc

In the context of the embargo imposed upon Palestinian belligerents—Jewish and Arab alike—and the dire lack of arms by the Yishuv in Palestine, Soviet ruler

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

's decision to breach the embargo and support the Yishuv with arms exported from

Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

played a role in the war that was differently appreciated. However, Syria also bought arms from Czechoslovakia for the

Arab Liberation Army

The Arab Liberation Army (ALA; ar, جيش الإنقاذ العربي ''Jaysh al-Inqadh al-Arabi''), also translated as Arab Salvation Army, was an army of volunteers from Arab countries led by Fawzi al-Qawuqji. It fought on the Arab side in the ...

, but the shipment never arrived due to Haganah intervention.

Possible motivations for Stalin's decision include his support of the UN Partition plan, and allowing Czechoslovakia to earn some foreign income after being forced to refuse

Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred over $13 billion (equivalent of about $ in ) in economic re ...

assistance.

The extent of this support and the concrete role that it played is up for debate. Figures advanced by historians tend to vary. Yoav Gelber spoke of 'small deliveries from Czechoslovakia arriving by air

..from April 1948 onwards' whereas various historians have argued that there was an unbalanced level of support in favor of

Yishuv

Yishuv ( he, ישוב, literally "settlement"), Ha-Yishuv ( he, הישוב, ''the Yishuv''), or Ha-Yishuv Ha-Ivri ( he, הישוב העברי, ''the Hebrew Yishuv''), is the body of Jewish residents in the Land of Israel (corresponding to the s ...

, given that the Palestinian Arabs did not benefit from an equivalent level of Soviet support. In any case, the embargo that was extended to all Arab states in May 1948 by the UN Security Council caused great problems to them.

Arab leaders' refusal of direct involvement

Arab leaders did what they could to avoid being directly involved in support for the Palestinian cause.

At the

Arab League

The Arab League ( ar, الجامعة العربية, ' ), formally the League of Arab States ( ar, جامعة الدول العربية, '), is a regional organization in the Arab world, which is located in Northern Africa, Western Africa, E ...

summit of October 1947, in

Aley

Aley ( ar, عاليه) is a major city in Lebanon. It is the capital of the Aley District and fourth largest city in Lebanon.

The city is located on Mount Lebanon, 15 km uphill from Beirut on the freeway to Damascus. Aley has the nick ...

, the Iraqi general, Ismail Safwat, painted a realist picture of the situation. He underlined the better organization and greater financial support of the Jewish people in comparison to the Palestinians. He recommended the immediate deployment of the Arab armies at the Palestinian borders, the dispatching of weapons and ammunition to the Palestinians, and the contribution of a million

pounds of financial aid to them. His proposals were rejected, other than the suggestion to send financial support, which was not followed up on.

Nonetheless, a techno-military committee was established to coordinate assistance to the Palestinians. Based in

Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metro ...

, it was directed by Sawfat, who was supported by Lebanese and Syrian officers and representatives of the Higher Arab Committee. A Transjordian delegate was also appointed, but he did not participate in meetings.

At the December 1947 Cairo summit, under pressure by public opinion, the Arab leaders decided to create a military command that united all the heads of all the major Arab states, headed by Safwat. They still ignored his calls for financial and military aid, preferring to defer any decision until the end of the Mandate,

[ Ilan Pappé (2000), p. 147] but, nevertheless, decide to form the

Arab Liberation Army

The Arab Liberation Army (ALA; ar, جيش الإنقاذ العربي ''Jaysh al-Inqadh al-Arabi''), also translated as Arab Salvation Army, was an army of volunteers from Arab countries led by Fawzi al-Qawuqji. It fought on the Arab side in the ...

, which would go into action in the following weeks.

On the night of 20–21 January 1948, around 700 armed Syrians entered Palestine via Transjordan. In February 1948, Safwat reiterated his demands, but they fell on deaf ears: the Arab governments hoped that the Palestinians, aided by the Arab Liberation Army, could manage on their own until the International community renounced the partition plan.

Arms problem

Civil war beginning (until 1 April 1948)

The

Arab Liberation Army

The Arab Liberation Army (ALA; ar, جيش الإنقاذ العربي ''Jaysh al-Inqadh al-Arabi''), also translated as Arab Salvation Army, was an army of volunteers from Arab countries led by Fawzi al-Qawuqji. It fought on the Arab side in the ...

was, in theory, financed and equipped by the

Arab League

The Arab League ( ar, الجامعة العربية, ' ), formally the League of Arab States ( ar, جامعة الدول العربية, '), is a regional organization in the Arab world, which is located in Northern Africa, Western Africa, E ...

. A budget of one million pounds sterling had been promised to them, due to the insistence of Ismail Safwat. In reality, though, funding never arrived, and only

Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

truly supported the Arab volunteers in concrete terms.

Syria bought from

Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

a quantity of arms for the

Arab Liberation Army

The Arab Liberation Army (ALA; ar, جيش الإنقاذ العربي ''Jaysh al-Inqadh al-Arabi''), also translated as Arab Salvation Army, was an army of volunteers from Arab countries led by Fawzi al-Qawuqji. It fought on the Arab side in the ...

but the shipment never arrived due to Hagana force intervention.

According to Lapierre & Collins, on the ground, logistics were completely neglected, and their leader, Fawzi al-Qawuqji, envisaged that his troops survive only on the expenses accorded to them by the Palestinian population. However, Gelber says that the Arab League had arranged the supplies through special contractors.

They were equipped with different types of light weapons, light and medium-sized mortars, a number of 75 mm and 105 mm guns, and armoured vehicles but their stock of shells was small.

The situation that the

Army of the Holy War and the Palestinian forces were in was worse. They could not rely on any form of foreign support and had to get by on the funds that

Mohammad Amin al-Husayni

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mono ...

could raise. The troops' armament was limited to what the fighters already had. To make things even worse, they had to be content with arms bought on the

black market or pillaged from British warehouses, and, as a result, did not really have enough arms to wage war.

Until March, Haganah suffered also a lack of arms. The Jewish fighters benefitted from a number of clandestine factories that manufactured some light weapons, ammunition and explosives. The one weapon of which there was no shortage was locally produced explosives. However, they had far less than what was necessary to carry out a war: in November, only one out of every three Jewish combatants was armed, rising to two out of three within Palmach.

Haganah sent agents to Europe and to the United States, in order to arm and equip this army.

To finance all of this,

Golda Meir

Golda Meir, ; ar, جولدا مائير, Jūldā Māʾīr., group=nb (born Golda Mabovitch; 3 May 1898 – 8 December 1978) was an Israeli politician, teacher, and ''kibbutznikit'' who served as the fourth prime minister of Israel from 1969 to 1 ...

managed, by the end of December, to collect $25 million through a fundraising campaign set about in the United States to capitalize on American sympathisers to the Zionist cause. Out of the 129 million US dollars raised between October 1947 and March 1949 for the Zionist cause, more than $78 million, over 60%, were used to buy arms and munition.

Death toll and analysis

In the last week of March alone, the losses sustained by Haganah were particularly heavy: they lost three large convoys in ambushes, more than 100 soldiers and their fleet of armoured vehicles.

All in all, West Jerusalem was gradually 'choked;' the settlements of Galilee could not be reached in any other way but via the valley of

Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Rive ...

and the road of

Nahariya. This along with the foreseen attack of the Arab states in May and the earlier projected departure date of the British pushed Haganah to the offensive and to apply

Plan Dalet

A plan is typically any diagram or list of steps with details of timing and resources, used to achieve an objective to do something. It is commonly understood as a temporal set of intended actions through which one expects to achieve a goal.

...

from April onwards.

Haganah on the offensive (1 April – 15 May 1948)

A leased transport plane was used for the

Operation Balak

Operation Balak was a smuggling operation, during the founding of Israel in 1948, that purchased arms in Europe to avoid various embargoes and boycotts transferring them to the Yishuv. Of particular note was the delivery of 23 Czechoslovakia-made ...

first arms ferry flight from

Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

on the end of March 1948. At the beginning of April 1948, a shipment of thousands of rifles and hundreds of machine guns arrived at Tel Aviv harbor. With this big shipment, Haganah could supply weapons to a concentrated effort, without taking over the arms of other Jewish territory and risking them being with no weapons.

Haganah went into the offensive, although still lacking heavy weapons.

In April, Yishuv forces began to resort to

biological warfare

Biological warfare, also known as germ warfare, is the use of biological toxins or infectious agents such as bacteria, viruses, insects, and fungi with the intent to kill, harm or incapacitate humans, animals or plants as an act of war. ...

in a top-secret operation called 'Cast Thy Bread', whose aim was to prevent the return of Palestinians to the villages Yishuv forces had conquered, and, as the practice reached beyond the key Tel-Aviv-Jerusalem lines, make conditions difficult for any Arab armies that might retake territory. This consisted in poisoning village wells. In the final months of the ensuing 1948 Arab-Israeli war, as Israel gained the upper hand, orders were apparently given to extend the use of biological agents against the Arab states themselves.

After 15 May 1948

After the Arab states invasion at 15 May, during the first weeks of the

1948 Arab–Israeli War

The 1948 (or First) Arab–Israeli War was the second and final stage of the 1948 Palestine war. It formally began following the end of the British Mandate for Palestine at midnight on 14 May 1948; the Israeli Declaration of Independence had ...

, the arms advantage leant in favour of the Arab states. From June, onwards, there was also a flow of heavy arms.

From June, after the first truce, the advantage leant clearly towards the Israelis. This situation's changing was due to the contacts made in November 1947 and afterwards.

The

Yishuv

Yishuv ( he, ישוב, literally "settlement"), Ha-Yishuv ( he, הישוב, ''the Yishuv''), or Ha-Yishuv Ha-Ivri ( he, הישוב העברי, ''the Hebrew Yishuv''), is the body of Jewish residents in the Land of Israel (corresponding to the s ...

purchased rifles,

machine gun

A machine gun is a fully automatic, rifled autoloading firearm designed for sustained direct fire with rifle cartridges. Other automatic firearms such as automatic shotguns and automatic rifles (including assault rifles and battle rifles) a ...

s and munitions from

Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

,

which were mainly supplied after the British navy blockade was lifted on 15 May 1948, at the end of the British mandate.

The Yishuv obtained from

Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

a supply of

Avia S-199 fighter planes too and, later on in the conflict,

Supermarine Spitfire

The Supermarine Spitfire is a British single-seat fighter aircraft used by the Royal Air Force and other Allied countries before, during, and after World War II. Many variants of the Spitfire were built, from the Mk 1 to the Rolls-Royce Grif ...

s. In the stockpiles left over from World War II, the

Yishuv

Yishuv ( he, ישוב, literally "settlement"), Ha-Yishuv ( he, הישוב, ''the Yishuv''), or Ha-Yishuv Ha-Ivri ( he, הישוב העברי, ''the Hebrew Yishuv''), is the body of Jewish residents in the Land of Israel (corresponding to the s ...

procured all the necessary equipment, vehicles and logistics needed for an army. In France, they procured armoured vehicles despite the ongoing embargo. The

Yishuv

Yishuv ( he, ישוב, literally "settlement"), Ha-Yishuv ( he, הישוב, ''the Yishuv''), or Ha-Yishuv Ha-Ivri ( he, הישוב העברי, ''the Hebrew Yishuv''), is the body of Jewish residents in the Land of Israel (corresponding to the s ...

bought machines to manufacture arms and munitions, forming the foundations of the Israeli armament industry.

The

Yishuv

Yishuv ( he, ישוב, literally "settlement"), Ha-Yishuv ( he, הישוב, ''the Yishuv''), or Ha-Yishuv Ha-Ivri ( he, הישוב העברי, ''the Hebrew Yishuv''), is the body of Jewish residents in the Land of Israel (corresponding to the s ...

bought at the United States, bombers and transport aircraft, which during

Operation Balak

Operation Balak was a smuggling operation, during the founding of Israel in 1948, that purchased arms in Europe to avoid various embargoes and boycotts transferring them to the Yishuv. Of particular note was the delivery of 23 Czechoslovakia-made ...

were used to ferry arms and dismantled

Avia S-199 fighter planes from

Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

to

Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

, in defiance of the

UN embargo, for 3 months, starting at 12 May 1948. Some ships were also leased out from various European ports so that these goods could be transported by 15 May.

However, for Ben-Gurion, the problem was also constructing an army that was worthy to be a state army.

Reorganisation of Haganah

After 'having gotten the Jews of Palestine and of elsewhere to do everything that they could, personally and financially, to help

Yishuv

Yishuv ( he, ישוב, literally "settlement"), Ha-Yishuv ( he, הישוב, ''the Yishuv''), or Ha-Yishuv Ha-Ivri ( he, הישוב העברי, ''the Hebrew Yishuv''), is the body of Jewish residents in the Land of Israel (corresponding to the s ...

,' Ben-Gurion's second greatest achievement was his having successfully transformed Haganah from being a clandestine

paramilitary organization into a true army. Ben-Gurion appointed

Israel Galili

Yisrael Galili ( he, ישראל גלילי; 10 February 1911 – 8 February 1986) was an Israeli politician, government minister and member of Knesset. Before Israel's independence in 1948, he served as Chief of Staff of the Haganah.

Biography

...

to the position of head of the High Command counsel of Haganah and divided Haganah into 6

infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and marine i ...

brigades, numbered 1 to 6, allotting a precise theatre of operation to each one. Yaakov Dori was named Chief of Staff, but it was Yigael Yadin who assumed the responsibility on the ground as chief of Operations. Palmach, commanded by

Yigal Allon

Yigal Allon ( he, יגאל אלון; 10 October 1918 – 29 February 1980) was an Israeli politician, commander of the Palmach, and general in the Israel Defense Forces, IDF. He served as one of the leaders of Ahdut HaAvoda party and the Labor P ...

, was divided into 3 elite brigades, numbered 10–12, and constituted the mobile force of Haganah. Ben-Gurion's attempts to retain personal control over the newly formed

IDF

IDF or idf may refer to:

Defence forces

* Irish Defence Forces

* Israel Defense Forces

*Iceland Defense Force, of the US Armed Forces, 1951-2006

* Indian Defence Force, a part-time force, 1917

Organizations

* Israeli Diving Federation

* Interac ...

lead later in July to

The Generals' Revolt

The Generals' Revolt was a series of confrontations between David Ben-Gurion and generals of the newly formed Israel Defense Forces (IDF) in 1948, on the eve of the establishment of the State of Israel.

The backdrop to the dispute was Ben Gurio ...

.

On 19 November 1947, obligatory

conscription

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day un ...

was instituted for all men and women aged between 17 and 25. By end of March 21,000 people had been conscripted. On 30 March the call-up was extended to men and single women aged between 26 and 35. Five days later a General Mobilization order was issued for all men under 40.

"From November 1947, the Haganah, (...) began to change from a territorial militia into a regular army. (...) Few of the units had been well trained by December. (...) By March–April, it fielded still under-equipped battalion and brigades. By April–May, the Haganah was conducting brigade size offensive."

War of the roads and blockade of Jerusalem

Geographic situation of the Jewish zones

Apart from on the coastline, Jewish

yishuv

Yishuv ( he, ישוב, literally "settlement"), Ha-Yishuv ( he, הישוב, ''the Yishuv''), or Ha-Yishuv Ha-Ivri ( he, הישוב העברי, ''the Hebrew Yishuv''), is the body of Jewish residents in the Land of Israel (corresponding to the s ...

im, or settlements, were very dispersed. Communication between the coastal area (the main area of Jewish settlements) and the peripheral settlements was by road. These road were an easy target for attacks, as most of them passed through or near entirely Arab localities. The isolation of the 100,000 Jewish people in

Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

and other Jewish settlements outside the coastal zone, such as kibbutz

Kfar Etzion

Kfar Etzion ( he, כְּפַר עֶצְיוֹן, ''lit.'' Etzion Village) is an Israeli settlement in the West Bank, organized as a religious kibbutz located in the Judean Hills between Jerusalem and Hebron in the southern West Bank, established ...

, halfway on the strategic road between Jerusalem and

Hebron

Hebron ( ar, الخليل or ; he, חֶבְרוֹן ) is a Palestinian. city in the southern West Bank, south of Jerusalem. Nestled in the Judaean Mountains, it lies above sea level. The second-largest city in the West Bank (after East J ...

, the 27 settlements in the southern region of

Negev

The Negev or Negeb (; he, הַנֶּגֶב, hanNegév; ar, ٱلنَّقَب, an-Naqab) is a desert and semidesert region of southern Israel. The region's largest city and administrative capital is Beersheba (pop. ), in the north. At its southe ...

[ Efraïm Karsh (2002), p. 34] and the settlements to the north of

Galilee

Galilee (; he, הַגָּלִיל, hagGālīl; ar, الجليل, al-jalīl) is a region located in northern Israel and southern Lebanon. Galilee traditionally refers to the mountainous part, divided into Upper Galilee (, ; , ) and Lower Galil ...

, were a strategic weakness for the Yishuv.

The possibility of evacuating these difficult to defend zones was considered, but the policy of

Haganah

Haganah ( he, הַהֲגָנָה, lit. ''The Defence'') was the main Zionist paramilitary organization of the Jewish population ("Yishuv") in Mandatory Palestine between 1920 and its disestablishment in 1948, when it became the core of the ...

was set by David Ben-Gurion. He stated that "what the Jewish people have has to be conserved. No Jewish person should abandon his or her house, farm,

kibbutz

A kibbutz ( he, קִבּוּץ / , lit. "gathering, clustering"; plural: kibbutzim / ) is an intentional community in Israel that was traditionally based on agriculture. The first kibbutz, established in 1909, was Degania. Today, farming h ...

or job without authorization. Every outpost, every colony, whether it is isolated or not, must be occupied as though it were

Tel Aviv

Tel Aviv-Yafo ( he, תֵּל־אָבִיב-יָפוֹ, translit=Tēl-ʾĀvīv-Yāfō ; ar, تَلّ أَبِيب – يَافَا, translit=Tall ʾAbīb-Yāfā, links=no), often referred to as just Tel Aviv, is the most populous city in the G ...

itself."

No Jewish settlement was evacuated until the invasion of May 1948. Only a dozen kibbutzim in Galilee, and those in Gush Etzion sent women and children into the safer interior zones.

Ben-Gurion gave instructions that the settlements of Negev be reinforced in number of men and goods,

in particular the kibbutzim of

Kfar Darom

Kfar Darom ( he, כְּפַר דָּרוֹם, ''lit.'' South Village), was a kibbutz and an Israeli settlement within the Gush Katif bloc in the Gaza Strip.

History

Kfar Darom was founded on 250 dunams of land (about 25 hectares or 60 acres) pu ...

and

Yad Mordechai

Yad Mordechai ( he, יַד מָרְדְּכַי, ''lit.'' Memorial of Mordechai) is a kibbutz in Southern Israel. Located 10 km (6.2 mi) south of Ashkelon, it falls under the jurisdiction of Hof Ashkelon Regional Council. In it had a popul ...

(both close to

Gaza),

Revivim

Revivim ( he, רְבִיבִים, , (rain) showers) is a kibbutz in the Negev desert in southern Israel. Located around half an hour south of Beersheba, it falls under the jurisdiction of Ramat HaNegev Regional Council. In it had a population of ...

(south of

Beersheba

Beersheba or Beer Sheva, officially Be'er-Sheva ( he, בְּאֵר שֶׁבַע, ''Bəʾēr Ševaʿ'', ; ar, بئر السبع, Biʾr as-Sabʿ, Well of the Oath or Well of the Seven), is the largest city in the Negev desert of southern Israel. ...

), and

Kfar Etzion

Kfar Etzion ( he, כְּפַר עֶצְיוֹן, ''lit.'' Etzion Village) is an Israeli settlement in the West Bank, organized as a religious kibbutz located in the Judean Hills between Jerusalem and Hebron in the southern West Bank, established ...

. Conscious of the danger that weighed upon Negev, the supreme command of

Haganah

Haganah ( he, הַהֲגָנָה, lit. ''The Defence'') was the main Zionist paramilitary organization of the Jewish population ("Yishuv") in Mandatory Palestine between 1920 and its disestablishment in 1948, when it became the core of the ...

assigned a whole

Palmach battalion there.

Siege of Jerusalem

Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

and the great difficulty of accessing the city became even more critical to its Jewish population, who made up one sixth of the total Jewish population in Palestine. The long and difficult route from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, after leaving the Jewish zone at

Hulda, went through the foothills of

Latrun

Latrun ( he, לטרון, ''Latrun''; ar, اللطرون, ''al-Latrun'') is a strategic hilltop in the Latrun salient in the Ayalon Valley, and a depopulated Palestinian village. It overlooks the road between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, 25 kilometers ...

. The 28-kilometre route between

Bab al-Wad and Jerusalem took no less than three hours, and the route passed near the Arab villages of

Saris

A sari (sometimes also saree or shari)The name of the garment in various regional languages include:

* as, শাৰী, xārī, translit-std=ISO

* bn, শাড়ি, śāṛi, translit-std=ISO

* gu, સાડી, sāḍī, translit-std= ...

,

Qaluniya,

Al-Qastal

Al-Qastal ("Kastel", ar, القسطل) was a Palestinian village located eight kilometers west of Jerusalem and named for a Crusader castle located on the hilltop. Used in 1948 during the Arab-Israeli War as a military base by the Army of the ...

, and

Deir Yassin

Deir Yassin ( ar, دير ياسين, Dayr Yāsīn) was a Palestinian Arab village of around 600 inhabitants about west of Jerusalem. Deir Yassin declared its neutrality during the 1948 Palestine war between Arabs and Jews. The village was razed ...

.

Abd al-Qadir al-Husayni

Abd al-Qadir al-Husayni ( ar, عبد القادر الحسيني), also spelled Abd al-Qader al-Husseini (1907 – 8 April 1948) was a Palestinian Arab nationalist and fighter who in late 1933 founded the secret militant group known as the Orga ...

arrived in Jerusalem with the intent to surround and besiege its Jewish community. He moved to

Surif, a village to the southwest of Jerusalem, with his supporters—around a hundred fighters who were trained in

Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

before the war and who served as officers in his army,

Jihad al-Muqadas, or Army of the Holy War. He was joined by a hundred or so young villagers and Arab veterans of the

British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

. His militia soon had several thousand men, and it moved its training quarters to

Bir Zeit, a town near

Ramallah.

Abd al-Qadir's zone of influence extended down to the area of

Lydda

Lod ( he, לוד, or fully vocalized ; ar, اللد, al-Lidd or ), also known as Lydda ( grc, Λύδδα), is a city southeast of Tel Aviv and northwest of Jerusalem in the Central District of Israel. It is situated between the lower Sheph ...

,

Ramleh

Ramla or Ramle ( he, רַמְלָה, ''Ramlā''; ar, الرملة, ''ar-Ramleh'') is a city in the Central District of Israel. Today, Ramle is one of Israel's mixed cities, with both a significant Jewish and Arab populations.

The city was f ...

, and the Judean Hills where

Hasan Salama

Hasan Salama or Hassan Salameh ( ar, حسن سلامة, ; 1913 – 2 June 1948) was a commander of the Palestinian Holy War Army (''Jaysh al-Jihad al-Muqaddas'', Arabic: ) in the 1948 Palestine War along with Abd al-Qadir al-Husayni.

Biograph ...

commanded 1,000 men. Salama, like Abd al-Qadir, had been affiliated with Mufti Haj Amin al Husseini for years, and had also been a commander in the

1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine

The 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine, later known as The Great Revolt (''al-Thawra al- Kubra'') or The Great Palestinian Revolt (''Thawrat Filastin al-Kubra''), was a popular nationalist uprising by Palestinian Arabs in Mandatory Palestine a ...

, participated in the

Rashid Ali

Rashid Ali al-Gaylaniin Arab standard pronunciation Rashid Aali al-Kaylani; also transliterated as Sayyid Rashid Aali al-Gillani, Sayyid Rashid Ali al-Gailani or sometimes Sayyad Rashid Ali el Keilany (" Sayyad" serves to address higher standing ...

coup of 1941 and the subsequent

Anglo-Iraqi War

The Anglo-Iraqi War was a British-led Allied military campaign during the Second World War against the Kingdom of Iraq under Rashid Gaylani, who had seized power in the 1941 Iraqi coup d'état, with assistance from Germany and Italy. The ca ...

.

Salama had re-entered Palestine in 1944 in

Operation Atlas, parachuting into the Jordan Valley as a member of a special German—Arab commando unit of the Waffen SS. He coordinated with al-Husayni to execute a plan of disruption and harassment of road traffic in an attempt to isolate and blockade Western (Jewish) Jerusalem.

[ Yoav Gelber (2006), p. 26]

On 10 December, the first organized attack occurred when ten members of a convoy between

Bethlehem

Bethlehem (; ar, بيت لحم ; he, בֵּית לֶחֶם '' '') is a city in the central West Bank, Palestine, about south of Jerusalem. Its population is approximately 25,000,Amara, 1999p. 18.Brynen, 2000p. 202. and it is the capital o ...

and

Kfar Etzion

Kfar Etzion ( he, כְּפַר עֶצְיוֹן, ''lit.'' Etzion Village) is an Israeli settlement in the West Bank, organized as a religious kibbutz located in the Judean Hills between Jerusalem and Hebron in the southern West Bank, established ...

were killed.

On 14 January, Abd al-Qadir himself commanded and took part in an attack against Kfar Etzion, in which 1,000 Palestinian Arab combatants were involved. The attack was a failure, and 200 of al-Husayni's men died. Nonetheless, the attack did not come without losses of Jewish lives: a detachment of

35 Palmach men who sought to reinforce the establishment were ambushed and killed.

On 25 January, a Jewish convoy was attacked near the Arab village of

al-Qastal

Al-Qastal ("Kastel", ar, القسطل) was a Palestinian village located eight kilometers west of Jerusalem and named for a Crusader castle located on the hilltop. Used in 1948 during the Arab-Israeli War as a military base by the Army of the ...

.

The attack went badly and several villages to the northeast of

Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

answered a call for assistance, although others did not, for fear of reprisals.

[ Yoav Gelber (2006), p. 27] The campaign for control over the roads became increasingly militaristic in nature, and became a focal point of the Arab war effort.

After 22 March, supply convoys to Jerusalem stopped, due to a convoy of around thirty vehicles having been destroyed in the

gorge

A canyon (from ; archaic British English spelling: ''cañon''), or gorge, is a deep cleft between escarpments or cliffs resulting from weathering and the erosion, erosive activity of a river over geologic time scales. Rivers have a natural tenden ...

s of Bab-el-Wad.

[ Pierre Razoux (2006), p. 66]

On 27 March, an important

supply convoy from

Kfar Etzion

Kfar Etzion ( he, כְּפַר עֶצְיוֹן, ''lit.'' Etzion Village) is an Israeli settlement in the West Bank, organized as a religious kibbutz located in the Judean Hills between Jerusalem and Hebron in the southern West Bank, established ...

was taken in an ambush in south of Jerusalem. They were forced to surrender all of their arms, ammunition and vehicles to al-Husayni's forces. The Jews of Jerusalem requested the assistance of the United Kingdom after 24 hours of combat. According to a British report, the situation in Jerusalem, where a food rationing system was already in application, risked becoming desperate after 15 May.

[ Efraïm Karsh (2002), p. 40]

The situation in other areas of the country was as critical as the one of Jerusalem. The settlements of Negev were utterly isolated, due to the impossibility of using the Southern coastal road, which passed through zones densely populated by Arabs.